A blog for people who like film and TV. Or just like reading about film and TV.

Sunday, December 15, 2013

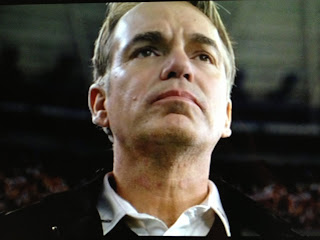

A Remembrance of Peter O'Toole

I knew this day would have to come.

I never quite knew what to say on occasions like this. I only know to say that there is no movie that I love as much as Lawrence of Arabia, and that it is impossible to imagine such a film without the talents of Peter O'Toole.

I recently lent a friend of mine my 50th Anniversary Blu-Ray set of Lawrence. And I can rest assured that the film, and the work of O'Toole in it and in countless other movies across his lengthy career, will continue to astound, excite, and inspire viewers for 50 years to come, and more.

I recently wrote about what I think is the almost singular status of O'Toole staggering performance as T.E. Lawrence. My piece, which also doubles as a tribute to Vivien Leigh, can be found here:

O'Hara and O'Toole/Lawrence and Leigh - Thoughts o...

Looking at the clip I posted above, I'm struck by the way that O'Toole is able to convey so many different levels of Lawrence depending on who is watching him -- how his performances evokes two completely polar sets of reactions, one from the officers and soldiers around Lawrence, and one from the audience watching in the theatre or at home. I love the weakness of his voice, softened by his recent trials and tribulations, combined with his character's inability to admit; the way he mixes the upright Edwardian English officer with the more primordial wanderer, a man who prefers to exist in the vacuum of a desert, "riding the whirlwind."

I could try to write about O'Toole's performance for hours, but in doing so I would scarcely begin to mine the depths of what he could do with his voice and his body, and in his oh-so-piercing eyes.

So instead, I will let Peter O'Toole himself talk about his acting. This following video is taken from a BBC program filmed in 1963, while O'Toole was performing Hamlet on stage for Laurence Olivier. Here, O'Toole, Orson Welles, and seasoned English stage actor Ernest Milton discuss the play, the character, and their interpretations of the same. It's riveting television, watching these professionals discuss their craft with verve and intelligence and a knowledge of what makes Prince Hamlet Prince Hamlet than dwarfs the opinions of those of us who have never tried to embody that role.

Look how passionate he is, how confident he is in his intimate knowledge of the Dane. That is an actor.

And so, perhaps it is appropriate to close with some words from Young Hamlet himself:

"If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain,

To tell my story."

But where O'Toole differs from Hamlet is that he needs no Horatio to remember him or tell his story. His accomplishments are all enshrined on celluloid. And the world is a little less harsh for it.

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

It's Back . . .

Hey, folks. Welcome back to RIDING THE WHIRLWIND following a longer-than-was-probably-necessary absence. Also back? The long awaited-return (with modifications) of the Netflix Pick of the Week, or as it now known, the STREAMING PICK OF THE WEEK.

With Netflix seeming to discard more and more of its film selections every day, a Netflix Pick of the Week felt awfully limiting. So now, I will be taking advantage of my Hulu Plus subscription to expand the confines of the feature, as well as taking into account that which can be found streaming on Amazon, YouTube, or other such services.

With that having been said, my next recommendation CAN be found on Netflix Instant Watch.

And that film is 1973's SERPICO.

Serpico is an odd mutt of a film.

It tells the story of Frank Serpico, played by Al Pacino in an early performance, a New York City police officer who slowly rises up through the ranks of the NYPD only to find institutional corruption, bureaucratic incompetence, and downright brutality all around him. He finds himself increasingly unable to stand by while witnessing the abuses of power taken on behalf of his fellow officers, and in doing so, places himself face-to-face from powerful and seemingly unbeatable forces.

Is it a cop movie? Well, yes, I suppose. By any objective definition it is a cop movie. The main character is a police officer and most of the people he interacts with are other police officers or criminals. But it lacks the typical cop movie goals or structures. There is no big case to crack, no mystery to solve, unless that mystery is "How can Frank Serpico do his duty as a peace officer when everyone around him is corrupt?"

Is it a biopic? Yes. By telling the true story of twelve years in the life of a real person the film should mark it as a biopic by any standard, but Serpico, directed by the late, great Sidney Lumet eschews the traditional rhythms and structures of the biopic in favor of a shaggy-dog almost Altman-esque vibe that initially provokes reactions of "Where are you going with this?" before one becomes used to and appreciative of the film's moody ambience. The thrust film's central plotline (Frank vs. corruption) does not even become clear until well into Serpico's 2 hour, 10 minute runtime.

What are the pleasures of Serpico? Plenty.

I won't be turning any heads, or shattering any firmly-planted monocles by saying this, but Sidney Lumet knew how to film New York City. The whole film is awash in the feel of the Old New York City, with its encounters in ethnic enclaves, its graffiti-coated walls, and its cold, rusted bridges and tenements. In fact, it looks rather like the Scorsese's contemporaneous Taxi Driver with that film's apocalyptic madman vision replaced with a journalist's eye for realism and the "big picture." One scene that has always stuck with me in particular is a conversation between Pacino and Tony Roberts' sympathetic cop that occurs on a spraypaint-splattered subway platform, where Lumet, along with director of photography Arthur J. Ornitz, using very few takes, allows the scene to play out in a subtle and naturalistic way that allows the viewer to take in either (or both) the dialogue between Pacino and Roberts, and the pre-gentrified urban environment that surrounds them.

The movie is absent of big stars, other than Pacino, instead utilizing a large cast of character actors whose beaten or besotted Irish and Italian faces form as much of the cityscape as the cabs and bodegas, while serving as the all-too-human gargoyles that watch over Serpico during his descent into a corrupt hell and his attempts to redeem and entire police force.

Pacino's performance reminds one of a time when it was the highpoint of a film when he began yelling and showing his anger, and not a seemingly contract-necessitated standby. He successfully demonstrates Frank Serpico's moral indignation and slowly-building frustration by hiding it for most of the film, allowing Serpico's external front as a 'go-along' beta male to project most clearly while subtly portraying the anger behind the eyes. And as the film goes on, that facade is slowly chipped away to reveal, at the end of the film, a man who has been both broken and emboldened by his experiences, as the compliant man turns to a man of passion.

The music, by Mikis Theodorakis, is an unusual element of the film, but one that I think works to the film's unlikely benefit. The Greek composer uses an sweeping, almost operatic score to lend a heroic air to the proceedings, one that almost could subvert the film's realist tone, but instead provides, at first, an ironic counterpoint to the squalidness of the world before going on to give the film's little-guy-against-the-world hero a romantic theme of his own, one of Frank's few victories in a world that refuses to grant him many.

Serpico seems to be an odd mutt of a film, a mostly singular mixture of seemingly clashing tones and styles. And perhaps it is. But when the mixture turns out to be this engrossing, when the pleasures are so many, then why would one complain?

Monday, October 28, 2013

Review - THE COUNSELOR

Mild spoilers for The Counselor follow:

THE COUNSELOR (2013)

Directed by Ridley Scott

Written by Cormac McCarthy

“I don't know what I thought about it. I still don't. It was too gynecological to be sexy."

-- 'Reiner' as played by Javier Bardem.

Is The Counselor a good movie?

Hmm. You'll have to come back to me on that one. Or not. I may be none the wiser about it in a month than I am now, having just seen it.

Is The Counselor a good movie when judged by the standards of a Typical Hollywood Crime Thriller? Certainly not. It's not even all that good when judged by the standards of your Offbeat/Auteur-Driven/Independent Crime Thriller.

It's a strange film, and I've been mulling over various comparisons ever since I walked out of the theatre, but none of them seem to stick. The most obvious comparison would be to No Country for Old Men, another unusual, philosophically-inclined Southwest-set thriller taken from the mind of Cormac McCarthy. But my reaction to The Counselor differed so much from my reaction to No Country that I can drawn one of two possibilities: either The Counselor is merely a failed version of the kind of film that No Country for Old Men successfully embodied, or The Counselor was aiming for something different, related but not the same, like the slightly maladjusted fraternal twin to No Country's model child.

While No Country for Old Men took the recognizable structure of a cat and mouse thriller and continually subverted it, depriving the audience of the "payoff" it was expecting, The Counselor completely saps the crime movie tropes of their typical meaning from the very start, demolishing the structures of the thriller until it leaves the viewer able to see the rubble, and recognize what it should look like when all the pieces are put together, but depriving the audience of any of the expected thrills or compelling moments that we have gone in to the theatre expecting. Unless what it is we were expecting was a treatise on the ultimate unknowability and isolation of all human beings in relation to each other, that is. But I doubt you were expecting that anyways. I certainly wasn't.

The plot, as it were, is almost totally indecipherable beyond the broadest outlines, and it was clear to me from watching that this is entirely by design. Michael Fassbender plays the unnamed central character -- The Counselor himself -- who invests in a border-crossing drug deal managed by Brad Pitt's hotshot Texan kingpin and Javier Bardem's gaudy businessman. The particulars of where the drugs where coming from, who they were going to, who was working for whom, and even exactly which drug it was that was being smuggled remain hazy and inchoate for the film's entire runtime, so I will not expend too much energy is describing the twists and turns of the deal and what goes wrong with it. Fassbender is engaged to a beautiful innocent played by Penelope Cruz, who does not play a virgin -- the first scene is an actually rather sensual lovemaking session between Fassbender and Cruz -- but who, for all intents and purposes, is positioned in the role of "The Virgin." Cameron Diaz is Javier Bardem's volatile girlfriend. There is some business involving Rosie Perez and a kid on a green motorcycle. Cartels are, of course, involved. John Leguizamo appears as well. Oh, and Edgar Ramirez is a priest, too.

If this summary makes the elements of the plot seem unconnected, well, that's because they are. In a linear, this-leads-to-that sense, that is. It has been said by some that in storytelling, all events must be told with "since..." or "but then..." instead of "and then..." but The Counselor ignores that. Every scene seems to introduce a new major character or subplot, and then the following scene seems to be entirely unrelated to the previous. This might be tenable for about 15-20 minutes of your typical movie, but The Counselor attempts to continue it for its entire run. What links these scenes, characters, and plotlines together is not the narrative, but rather Cormac McCarthy's pervading worldview. All the characters -- with perhaps one exception -- speak with one voice, and it is McCarthy's. The dialogue is not dialogue in the way we usually think of it, where characters meet on a agreed common ground and attempt to get across their wants and desires while being in some level of conflict or chemistry with the other character. The characters in The Counselor tend to speak past each other, and when they are in dialogue, the audience generally has no idea what they're talking about. There is almost no audience identification with any character. Most characters are entirely unpleasant and their desires extend no further than basic animal greed. We don't really want to see The Counselor himself get hurt, but we don't really root for him either. It is only his love for his Laura that keeps him from being entirely a cold cipher, and their romance (Fassbender and Cruz do have some real chemistry) is the only ray of light in a film that is otherwise entirely dark and bleak, tonally and emotionally. Long sequences go by where characters perform tasks we don't recognize, for purpose that we do not know; we are locked out of understanding the meaning of the scene that plays out before us.

What does one do with the writing? Since the plot should be thrown out, as it's clear neither Scott nor McCarthy are all that interested in it, the dialogue and speeches are basically all we have to judge. . Most screenwriters, even the best, are more like the people who design the rides at Disneyland than capital-A Authors -- they conceive and realize the moments that the audience is made to experience. They have to understand their characters' psychology, and chart out the plots, often utilizing fun and witty dialogue to make the medicine go down easy. Well, McCarthy is a different kind of writer, a man of letters, someone whose prose has been studied in universities and awards committees the world over. But does that mean his writing adapts well to the screen in this, his first original screenplay? Yes and no. McCarthy's highly arch and often florid dialogue would no doubt read very well, but it is not served by Scott's decision to fill his cast with actors who either are not speaking their native language (Bardem, Cruz, Bruno Ganz) or are made to speak in an accent that is not their own (Fassbender, Perez). And the dialogue may have gone by too fast to really connect in some scenes. But that might even be by design. The film ceaselessly pushes the viewer away in almost every other aspect, so why not in this one as well? Most of the speeches -- which function only as speeches, as authorial soapboxes -- are eloquently ominous, and most scenes do not end without a memorable line or snippet of dialogue, yet this isn't a film like, say, Lincoln or The Social Network, where the words are so listenable, so rhythmic that they are a thrill ride unto themselves. There is one big monologue (near monologue, actually) towards the end that is as close to the film's thesis statement as one will get, and it is beautiful, genuinely poetic and clearly coming from a place of real thought and pain. Out of context I would guess it has just as much power as within the film itself. But is that a problem? Shouldn't it have more meaning when it has the whole of the film behind it than when it is just taken in a vacuum? The character delivering it has no real reason to say it other than the fact that it is something that Cormac McCarthy would like to be said. Is that enough?

I don't know if I could say.

There are parts of the film that are real misfires, regardless of intent. Diaz is, frankly, outmatched by her role, which is a shame because so much of the film's thematic points hinge around her character. Scott, perhaps slightly afraid, backs off from the uncompromising tone in a few scenes towards the end, asking the audience to feel for The Counselor when previously the film had been content to regard him with only pity, like a deer hit by a truck on the highway; in another film this might be fine, but it doesn't mesh with the overall perspective here. The score, by Daniel Pemberton, is the biggest misstep of them all, as it attempts to push the film towards a typical thriller even while all the rest of the film subverts or avoids the beats of a normal thriller.

But I do think, that when one gets right down to it, The Counselor is trying to do something that few other movies I have ever seen, if any, have attempted to do. Perhaps this is why the critical reaction has often been so negative. I worry sometimes that I write too much about how critics react to things, and not about the films themselves, but with The Counselor, to discuss the effect it has on people is to discuss the movie itself. It wants to create a cold, often unpleasant experience -- where there is no beauty or grotesque humor shaped out of the ugliness -- with the hope that out of the experience you will come to understand or be made to understand some of McCarthy's deeply held truths.

Can I recommend The Counselor? I think most people will leave the film feeling deeply unsatisfied. But I doubt McCarthy cares if we are satisfied. Even with a film like No Country for Old Men, where critics raved of its avoidance of "closure" and "satisfaction," the Coen Brothers were clearly having a great deal of fun directing it, and that sense of excitement was palpable and contagious for the audience. Here, the craft is decidedly more understated. We leave The Counselor not basking in the pure expertise of the filmmakers, alive with the elation of the possibilities of film; instead we feel as if we have inhabited another man's headspace for two hours, and fear that that headspace is closer to the world we live in than the way we felt walking in.

THE COUNSELOR (2013)

Directed by Ridley Scott

Written by Cormac McCarthy

“I don't know what I thought about it. I still don't. It was too gynecological to be sexy."

-- 'Reiner' as played by Javier Bardem.

Is The Counselor a good movie?

Hmm. You'll have to come back to me on that one. Or not. I may be none the wiser about it in a month than I am now, having just seen it.

Is The Counselor a good movie when judged by the standards of a Typical Hollywood Crime Thriller? Certainly not. It's not even all that good when judged by the standards of your Offbeat/Auteur-Driven/Independent Crime Thriller.

It's a strange film, and I've been mulling over various comparisons ever since I walked out of the theatre, but none of them seem to stick. The most obvious comparison would be to No Country for Old Men, another unusual, philosophically-inclined Southwest-set thriller taken from the mind of Cormac McCarthy. But my reaction to The Counselor differed so much from my reaction to No Country that I can drawn one of two possibilities: either The Counselor is merely a failed version of the kind of film that No Country for Old Men successfully embodied, or The Counselor was aiming for something different, related but not the same, like the slightly maladjusted fraternal twin to No Country's model child.

While No Country for Old Men took the recognizable structure of a cat and mouse thriller and continually subverted it, depriving the audience of the "payoff" it was expecting, The Counselor completely saps the crime movie tropes of their typical meaning from the very start, demolishing the structures of the thriller until it leaves the viewer able to see the rubble, and recognize what it should look like when all the pieces are put together, but depriving the audience of any of the expected thrills or compelling moments that we have gone in to the theatre expecting. Unless what it is we were expecting was a treatise on the ultimate unknowability and isolation of all human beings in relation to each other, that is. But I doubt you were expecting that anyways. I certainly wasn't.

The plot, as it were, is almost totally indecipherable beyond the broadest outlines, and it was clear to me from watching that this is entirely by design. Michael Fassbender plays the unnamed central character -- The Counselor himself -- who invests in a border-crossing drug deal managed by Brad Pitt's hotshot Texan kingpin and Javier Bardem's gaudy businessman. The particulars of where the drugs where coming from, who they were going to, who was working for whom, and even exactly which drug it was that was being smuggled remain hazy and inchoate for the film's entire runtime, so I will not expend too much energy is describing the twists and turns of the deal and what goes wrong with it. Fassbender is engaged to a beautiful innocent played by Penelope Cruz, who does not play a virgin -- the first scene is an actually rather sensual lovemaking session between Fassbender and Cruz -- but who, for all intents and purposes, is positioned in the role of "The Virgin." Cameron Diaz is Javier Bardem's volatile girlfriend. There is some business involving Rosie Perez and a kid on a green motorcycle. Cartels are, of course, involved. John Leguizamo appears as well. Oh, and Edgar Ramirez is a priest, too.

If this summary makes the elements of the plot seem unconnected, well, that's because they are. In a linear, this-leads-to-that sense, that is. It has been said by some that in storytelling, all events must be told with "since..." or "but then..." instead of "and then..." but The Counselor ignores that. Every scene seems to introduce a new major character or subplot, and then the following scene seems to be entirely unrelated to the previous. This might be tenable for about 15-20 minutes of your typical movie, but The Counselor attempts to continue it for its entire run. What links these scenes, characters, and plotlines together is not the narrative, but rather Cormac McCarthy's pervading worldview. All the characters -- with perhaps one exception -- speak with one voice, and it is McCarthy's. The dialogue is not dialogue in the way we usually think of it, where characters meet on a agreed common ground and attempt to get across their wants and desires while being in some level of conflict or chemistry with the other character. The characters in The Counselor tend to speak past each other, and when they are in dialogue, the audience generally has no idea what they're talking about. There is almost no audience identification with any character. Most characters are entirely unpleasant and their desires extend no further than basic animal greed. We don't really want to see The Counselor himself get hurt, but we don't really root for him either. It is only his love for his Laura that keeps him from being entirely a cold cipher, and their romance (Fassbender and Cruz do have some real chemistry) is the only ray of light in a film that is otherwise entirely dark and bleak, tonally and emotionally. Long sequences go by where characters perform tasks we don't recognize, for purpose that we do not know; we are locked out of understanding the meaning of the scene that plays out before us.

What does one do with the writing? Since the plot should be thrown out, as it's clear neither Scott nor McCarthy are all that interested in it, the dialogue and speeches are basically all we have to judge. . Most screenwriters, even the best, are more like the people who design the rides at Disneyland than capital-A Authors -- they conceive and realize the moments that the audience is made to experience. They have to understand their characters' psychology, and chart out the plots, often utilizing fun and witty dialogue to make the medicine go down easy. Well, McCarthy is a different kind of writer, a man of letters, someone whose prose has been studied in universities and awards committees the world over. But does that mean his writing adapts well to the screen in this, his first original screenplay? Yes and no. McCarthy's highly arch and often florid dialogue would no doubt read very well, but it is not served by Scott's decision to fill his cast with actors who either are not speaking their native language (Bardem, Cruz, Bruno Ganz) or are made to speak in an accent that is not their own (Fassbender, Perez). And the dialogue may have gone by too fast to really connect in some scenes. But that might even be by design. The film ceaselessly pushes the viewer away in almost every other aspect, so why not in this one as well? Most of the speeches -- which function only as speeches, as authorial soapboxes -- are eloquently ominous, and most scenes do not end without a memorable line or snippet of dialogue, yet this isn't a film like, say, Lincoln or The Social Network, where the words are so listenable, so rhythmic that they are a thrill ride unto themselves. There is one big monologue (near monologue, actually) towards the end that is as close to the film's thesis statement as one will get, and it is beautiful, genuinely poetic and clearly coming from a place of real thought and pain. Out of context I would guess it has just as much power as within the film itself. But is that a problem? Shouldn't it have more meaning when it has the whole of the film behind it than when it is just taken in a vacuum? The character delivering it has no real reason to say it other than the fact that it is something that Cormac McCarthy would like to be said. Is that enough?

I don't know if I could say.

There are parts of the film that are real misfires, regardless of intent. Diaz is, frankly, outmatched by her role, which is a shame because so much of the film's thematic points hinge around her character. Scott, perhaps slightly afraid, backs off from the uncompromising tone in a few scenes towards the end, asking the audience to feel for The Counselor when previously the film had been content to regard him with only pity, like a deer hit by a truck on the highway; in another film this might be fine, but it doesn't mesh with the overall perspective here. The score, by Daniel Pemberton, is the biggest misstep of them all, as it attempts to push the film towards a typical thriller even while all the rest of the film subverts or avoids the beats of a normal thriller.

But I do think, that when one gets right down to it, The Counselor is trying to do something that few other movies I have ever seen, if any, have attempted to do. Perhaps this is why the critical reaction has often been so negative. I worry sometimes that I write too much about how critics react to things, and not about the films themselves, but with The Counselor, to discuss the effect it has on people is to discuss the movie itself. It wants to create a cold, often unpleasant experience -- where there is no beauty or grotesque humor shaped out of the ugliness -- with the hope that out of the experience you will come to understand or be made to understand some of McCarthy's deeply held truths.

Can I recommend The Counselor? I think most people will leave the film feeling deeply unsatisfied. But I doubt McCarthy cares if we are satisfied. Even with a film like No Country for Old Men, where critics raved of its avoidance of "closure" and "satisfaction," the Coen Brothers were clearly having a great deal of fun directing it, and that sense of excitement was palpable and contagious for the audience. Here, the craft is decidedly more understated. We leave The Counselor not basking in the pure expertise of the filmmakers, alive with the elation of the possibilities of film; instead we feel as if we have inhabited another man's headspace for two hours, and fear that that headspace is closer to the world we live in than the way we felt walking in.

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Truth, Justice, and the (White?) American Way

Over

the past decade or so, the major Hollywood studios have increased their

output of superhero movies greatly, and not a summer goes by without a

major motion picture adapted from a comic book superhero franchise.

These movies almost always make the list of the top grossing films of

the year, with profits well into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

They are seen by millions, possibly even billions, around the globe.

By my count, there have been nearly 50 movies based on comic book superheroes since the turn of the millennium.

The last comic book superhero movie released by a major studio whose LEAD character (not a sidekick) was black was back in 2004 -- nine years ago -- with BLADE: TRINITY (if that even counts as a superhero movie) and CATWOMAN starring Halle Berry. If you're discounting the Blade movies, and regarding Catwoman as a spin-off from the Batman franchise, and instead asking for the most recent movie to introduce a leading black superhero before 2004, you'd have to go all the way back to 1997, with the release of the movie STEEL starring Shaquille O'Neal. In other words, the last major movie to introduce a black superhero is now older than the average superhero movie fan.

The last movie to star a female superhero was ELEKTRA from 2005 -- eight years ago. That and CATWOMAN were the only woman-led superhero movies to come out since X-MEN kickstarted the current wave back in 2000. In other words, by the time of the release of the new Superman vs. Batman movie, there will have been twice as many movies starring a single male character (Batman) then there will have been starring an individual of the gender that makes of 50% of the planet.

You might be reading this, saying, "But Michael, no ones care about the female or nonwhite superheroes! They're not good characters! The studios only make movies about popular, famous characters, like Batman and Superman!"

Yes, because people were *clamoring* for GHOST RIDER. And GHOST RIDER 2.

And JONAH HEX.

And the GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY.

And KICK-ASS. And KICK-ASS 2, evidently.

And R.I.P.D.

And WANTED.

And THE GREEN HORNET.

And...

Can any of you out there who aren't huge comic book fans genuinely say that you were big Iron Man fans before Robert Downey Jr. stepped into the role?

And can any of you honestly say that you've never heard of the *totally obscure* character Wonder Woman?

And if you say, what does it matter, they're just movies -- think about the effect that movies have on kids and teenagers, who are probably the main audience for superhero movies. Think about how people are still religiously obsessed with STAR WARS even though there hasn't been an all around solid Star Wars movies since Jimmy Carter was President. Think about how kids look up to superheroes, how they see them as role models, how they want to be like them. Nonwhite kids who go to the movies have no superhero out there that looks like them. White kids have dozens. Girls have no superhero out there that looks like them. Boys have dozens and dozens.

If you think that doesn't matter, then I don't know what to tell you... you probably shouldn't be checking out this blog in that case, as I'm not interested in having readers who don't think films or the film industry matter. They can go to the IMDb message boards and hear their own fan-boy opinion parroted back at them if that's what they prefer.

By my count, there have been nearly 50 movies based on comic book superheroes since the turn of the millennium.

The last comic book superhero movie released by a major studio whose LEAD character (not a sidekick) was black was back in 2004 -- nine years ago -- with BLADE: TRINITY (if that even counts as a superhero movie) and CATWOMAN starring Halle Berry. If you're discounting the Blade movies, and regarding Catwoman as a spin-off from the Batman franchise, and instead asking for the most recent movie to introduce a leading black superhero before 2004, you'd have to go all the way back to 1997, with the release of the movie STEEL starring Shaquille O'Neal. In other words, the last major movie to introduce a black superhero is now older than the average superhero movie fan.

The last movie to star a female superhero was ELEKTRA from 2005 -- eight years ago. That and CATWOMAN were the only woman-led superhero movies to come out since X-MEN kickstarted the current wave back in 2000. In other words, by the time of the release of the new Superman vs. Batman movie, there will have been twice as many movies starring a single male character (Batman) then there will have been starring an individual of the gender that makes of 50% of the planet.

You might be reading this, saying, "But Michael, no ones care about the female or nonwhite superheroes! They're not good characters! The studios only make movies about popular, famous characters, like Batman and Superman!"

Yes, because people were *clamoring* for GHOST RIDER. And GHOST RIDER 2.

And JONAH HEX.

And the GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY.

And KICK-ASS. And KICK-ASS 2, evidently.

And R.I.P.D.

And WANTED.

And THE GREEN HORNET.

And...

Can any of you out there who aren't huge comic book fans genuinely say that you were big Iron Man fans before Robert Downey Jr. stepped into the role?

And can any of you honestly say that you've never heard of the *totally obscure* character Wonder Woman?

And if you say, what does it matter, they're just movies -- think about the effect that movies have on kids and teenagers, who are probably the main audience for superhero movies. Think about how people are still religiously obsessed with STAR WARS even though there hasn't been an all around solid Star Wars movies since Jimmy Carter was President. Think about how kids look up to superheroes, how they see them as role models, how they want to be like them. Nonwhite kids who go to the movies have no superhero out there that looks like them. White kids have dozens. Girls have no superhero out there that looks like them. Boys have dozens and dozens.

If you think that doesn't matter, then I don't know what to tell you... you probably shouldn't be checking out this blog in that case, as I'm not interested in having readers who don't think films or the film industry matter. They can go to the IMDb message boards and hear their own fan-boy opinion parroted back at them if that's what they prefer.

Saturday, September 28, 2013

O'Hara and O'Toole/Lawrence and Leigh - Thoughts on the twin titans of movie acting

For

me, the two greatest achievements of film acting are Vivien Leigh in

"Gone with the Wind" and Peter O'Toole in "Lawrence of Arabia."

If you were to rank every performance in every film (if such a list could even be useful), I don't know what exactly would be number one, but it would begin with these two and then everyone else. You could teach whole classes on acting just based on them.

And there are a surprising number of similarities between the two.

Both were not-very-well-known British stage actors who were given starring roles in giant Hollywood productions, beating out big name stars for the part.

Both were young, in their 20s. Leigh was 25 during filming, O'Toole was 28.

Both movies are epics. I mean LONG, about 4 hours.

Think about how important their voices are to the characters: Leigh's Southern belle drawl with its "fiddle-dee-dee" rhythms; O'Toole's watery, wavering tenor. And their trademark facial expressions: Leigh's calculating pout, O'Toole's withering stare.

Both incorporate what Jung would call their anima and animus: the expressions of their feminine and masculine inner personalities. Scarlett O'Hara is a lady, yes, but not a proper one, bristling at the assumptions of the Southern patriarchy, taking charge, not relying on a man, but using them for her own goals. Lawrence is the military hero of the British empire, but he preens and admires his perfect white robes, bonding with his men with a tender devotion not shared by his cold-hearted superiors.

Both show arrogance, and total despair. They're both despicable and admirable. Villains, heroes, victims, oppressors.

These two roles, in their dynamism and their depth, represent the complexities of cinematic acting, the role of the human being in film art. They're our Hamlet.

If you were to rank every performance in every film (if such a list could even be useful), I don't know what exactly would be number one, but it would begin with these two and then everyone else. You could teach whole classes on acting just based on them.

And there are a surprising number of similarities between the two.

Both were not-very-well-known British stage actors who were given starring roles in giant Hollywood productions, beating out big name stars for the part.

Both were young, in their 20s. Leigh was 25 during filming, O'Toole was 28.

Both movies are epics. I mean LONG, about 4 hours.

Think about how important their voices are to the characters: Leigh's Southern belle drawl with its "fiddle-dee-dee" rhythms; O'Toole's watery, wavering tenor. And their trademark facial expressions: Leigh's calculating pout, O'Toole's withering stare.

Both incorporate what Jung would call their anima and animus: the expressions of their feminine and masculine inner personalities. Scarlett O'Hara is a lady, yes, but not a proper one, bristling at the assumptions of the Southern patriarchy, taking charge, not relying on a man, but using them for her own goals. Lawrence is the military hero of the British empire, but he preens and admires his perfect white robes, bonding with his men with a tender devotion not shared by his cold-hearted superiors.

Both show arrogance, and total despair. They're both despicable and admirable. Villains, heroes, victims, oppressors.

These two roles, in their dynamism and their depth, represent the complexities of cinematic acting, the role of the human being in film art. They're our Hamlet.

Saturday, September 14, 2013

And One Day There Will Be No More

Apropos of nothing in particular...

SPOILERS FOR THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS FOLLOW

"The frontier moves with the sun and pushes the Red Man of these wilderness forests in front of it, until one day there will be nowhere left. Then our race will be no more, or be not us. [ . . . ] The frontier place is for people like my white son and his woman and their children. And one day there will be no more frontier. Then men like you will go, too. Like the Mohicans. And new people will come. Work, struggle. Some will make their life.

But once . . . we were here."

-- The Last of the Mohicans (Expanded Version), screenplay by Michael Mann and Christopher Crowe.

These are the last words spoken in the film. The old chief Chingachgook, both the last father and the last son of a proud and dying nation (played with weight and authority by Russell Means, a real life indigenous rights activist making his acting debut) looks forward into what he believes to be the future of his people, and of all peoples.

The director's expanded version seen on DVD was the cut that introduced me to this film, and it absolutely confounds that anyone (director Mann, editors Dov Hoenig and Arthur Schmidt, or even 20th Century Fox executives) could have thought that a version of the film without these lines would be preferable to one with them. But someone must have felt otherwise, as the film was released theatrically with this quote admitted.

Regardless, these lines are out and available now, and thus are completely vulnerable to my dubious praise.

As someone who has had considerable background in the study of history and has worked in the museums, and as simply a lover of history and all its glorious paradoxes, I can hardly think of a better, more succinct way of describing the appeal of history, of the vast past that rests behind us but refuses to recede from us. In this moment, as Means and actors Daniel Day-Lewis and Madeleine Stowe, huddled together for warmth and comfort, look out over the fog-covered mountains, mountains older than any one of them, older than the French or British Empires, older than the Mohican Tribe, mountains that will continue to exist until the day man hubristically decides he has no more need for them, the film perfectly captures that unique sense one has of history, that the past -- and all it consists of -- remains both entirely impermanent and inescapably present.

In short, Michael Mann needs to make another period film. Get crackin' on Azincourt, Mike.

SPOILERS FOR THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS FOLLOW

"The frontier moves with the sun and pushes the Red Man of these wilderness forests in front of it, until one day there will be nowhere left. Then our race will be no more, or be not us. [ . . . ] The frontier place is for people like my white son and his woman and their children. And one day there will be no more frontier. Then men like you will go, too. Like the Mohicans. And new people will come. Work, struggle. Some will make their life.

But once . . . we were here."

-- The Last of the Mohicans (Expanded Version), screenplay by Michael Mann and Christopher Crowe.

These are the last words spoken in the film. The old chief Chingachgook, both the last father and the last son of a proud and dying nation (played with weight and authority by Russell Means, a real life indigenous rights activist making his acting debut) looks forward into what he believes to be the future of his people, and of all peoples.

The director's expanded version seen on DVD was the cut that introduced me to this film, and it absolutely confounds that anyone (director Mann, editors Dov Hoenig and Arthur Schmidt, or even 20th Century Fox executives) could have thought that a version of the film without these lines would be preferable to one with them. But someone must have felt otherwise, as the film was released theatrically with this quote admitted.

Regardless, these lines are out and available now, and thus are completely vulnerable to my dubious praise.

As someone who has had considerable background in the study of history and has worked in the museums, and as simply a lover of history and all its glorious paradoxes, I can hardly think of a better, more succinct way of describing the appeal of history, of the vast past that rests behind us but refuses to recede from us. In this moment, as Means and actors Daniel Day-Lewis and Madeleine Stowe, huddled together for warmth and comfort, look out over the fog-covered mountains, mountains older than any one of them, older than the French or British Empires, older than the Mohican Tribe, mountains that will continue to exist until the day man hubristically decides he has no more need for them, the film perfectly captures that unique sense one has of history, that the past -- and all it consists of -- remains both entirely impermanent and inescapably present.

In short, Michael Mann needs to make another period film. Get crackin' on Azincourt, Mike.

Sunday, September 8, 2013

Intermission

Sorry of the lack of posts lately. But soon enough I'll be back with more new material.

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

BEN-HUR and the Power of Icons

No Netflix pick this week. Instead, here's a piece inspired by 1925's Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.

The spoken parts are practically always the worst part of any historical epic. Try, if you can, to recite more than a few lines of dialogue from any one of the famous Biblical/ancient epics of the '50s. It simply can't be done. Beyond the occasional one-liner -- think "I am Spartacus" -- the dialogue in films such as The Ten Commandments, Quo Vadis, and the 1959 version of Ben-Hur (and modern day descendants such as Gladiator) consists mainly of stilted, wooden declarations where characters seem to be talking past or at each other, rather than with each other. Watching such scenes one cannot help but either roll their eyes and wait for the chariot racing scenes; either that or to devote all of one's attention to the expensive costumes and sets. Perhaps the reason the makers of Cleopatra gave Liz Taylor so many outfits to wear was solely to distract from the fact that you're not listening to verse.

The spoken parts are practically always the worst part of any historical epic. Try, if you can, to recite more than a few lines of dialogue from any one of the famous Biblical/ancient epics of the '50s. It simply can't be done. Beyond the occasional one-liner -- think "I am Spartacus" -- the dialogue in films such as The Ten Commandments, Quo Vadis, and the 1959 version of Ben-Hur (and modern day descendants such as Gladiator) consists mainly of stilted, wooden declarations where characters seem to be talking past or at each other, rather than with each other. Watching such scenes one cannot help but either roll their eyes and wait for the chariot racing scenes; either that or to devote all of one's attention to the expensive costumes and sets. Perhaps the reason the makers of Cleopatra gave Liz Taylor so many outfits to wear was solely to distract from the fact that you're not listening to verse.

The fundamental question in constructing this dialogue is that of appropriateness. One can either have their characters speak in contemporary Hollywood dialect or in a faux-archaic parlance intended to approximate the speech of ancient Greeks, Romans, or Jews. The problem with both approaches is obvious. If Julius Caesar is not only speaking English but is sounding like a 20th century Hollywood movie producer, than the viewer can hardly be expected to believe he's watching Julius Caesar. Alternatively, giving your characters phony formalized speech usually sounds pompous and overreaching. Even the best Hollywood scribes are not Shakespeare, and "Yonder lies the castle of my faddah" is no "The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves."

Take for instance, this passage describing the development of 1959's Ben-Hur, taken from Wikipedia.

"[Screenwriter Christopher] Fry gave the dialogue a slightly more formal and archaic tone without making it sound stilted and medieval. For example, the sentence "How was your dinner?" became "Was the food not to your liking?"

The line "How was your dinner?" is boring. The line "Was the food not to your liking?" is somewhat less boring. It also feels much less natural. This strikes me as more of a lateral move than anything.

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ avoids this problem by virtue of being, of course, a silent film. To be sure, there are still intertitles, and they are usually written in the same flowery, pseudo-poetic hokum tone as in the films sound-era spiritual successors. But it is much less irritating to read such lines than to hear actors try and get their mouths around them.

Instead, the silent Ben-Hur uses certain images -- most made iconic through centuries of collective fascination with Ancient Rome and the story of Christ -- to great effect. Forcefully told by director Fred Niblo, the film is not subtle. Indeed, if one could only tell its villain Messala* (Francis X. Bushman) that Roman officers were now allowed to grow facial hair, I'm sure he would immediately grow out a thick handlebar mustache for the sole purpose of twirling it. No, Ben-Hur has no real desire, or need, for nuance. It derives its power from the strength of its images -- icons, really, religious and all -- and it tells its story and its message with purpose, with conviction, and with great flavor.

*He also bears an uncannily strong resemblance to comedian Ken Marino. Seriously.

I'd really like to get across how enjoyable, how exciting, how alluring this film is. But I think many ways of trying to describe its strengths would be utterly wrong. Talking about the Kuleshov effect, or auteur theory, or the dynamics of its plot would be useless when discussing this film. like trying to figure out how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. It would do nothing to get across what the experience of watching this film is like.

Instead, I'm going to take a page from the Roger Ebert playbook, specifically his brilliant and beautiful review of Stormy Monday -- as seen here: http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/stormy-monday-1988 -- and talk about the icons seen in this film, from manger to the cross.

Ben-Hur is about living tableaus of Christian iconography. The young virgin mother cradling an unseen babe in the middle of the stable, with shepherds around her indistinguishable from parishioners gathered in pews. It about the cold wooden beams of a cross passing lifted above a crowd, who can choose to like upon the sight with pity or derision.

It also about a man being tied to the mast of a pirate ship, screaming in agony as he himself is used as a weapon against his fellow countrymen, battering their ship with a force beyond his control. It is about the vengeance-darkened eyes of a man, born into privilege, who has come to know hunger and slavery as he pushes the massive oars of a slave galley, driven by an anger that recognizes no life, only death.

It is about the days that look like they've been dipped in amber. It is about the nights painted with a cool, soft blue. It is about moments when it appears that everything has become alight, and filled with color, even if such moments are only brief before one realizes that its just two-strip Technicolor.

Ben-Hur is about the old miser, hunched over and haggard. It is about the fat, grinning faces of greedy Romans. It is about the Egyptian seductress's half-naked body and flimsy costume -- almost as sexy as Anna May Wong in The Thief of Bagdad. Almost.

Ben-Hur is about the best damn chariot race you'll ever see.

Ben-Hur is a winged helmet.

Ben-Hur is four white horses.

Ben-Hur is the bruised face of a disgraced loser.

Ben-Hur is about a mother running her hand just above her sleeping son's head, unwilling to wake him, but wishing to cradle and comfort him as if he were still the infant she once nursed, and not the grown man who lays before her.

And that is why 1925's Ben-Hur is more of an epic than most films will ever be.

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

NETFLIX PICK OF THE WEEK - Velvet Goldmine

This week's movie is Todd Haynes' modern classic Velvet Goldmine.

I'm going to try and keep this one relatively brief, because I plan on writing a much, much longer piece on this film at some later point. Why, then, should I even bring up Velvet Goldmine? Because it's that damn good.

At one point in Velvet Goldmine, a pretentious young glam-rock fan declares to an even younger, much greener glam kid that he "prefers impressions to ideas."

This film does not prefer impressions to ideas. This is a film whose ideas are so strong, so variate, and yet all in service of a single point-of-view.

This film says more about the power of music and the love of music than the plethora of factory-made musical biopics that are trotted out every year by the studios.

The reception to Velvet Goldmine has been fairly cool and unenthusiastic since it was first released in 1998, and I think I know the reason. The film is often, mostly inaccurately, described as a movie about David Bowie, and Goldmine is a weak biography if viewed as one. But it's not a biography, certainly not one of Bowie. This film tells you very little about what makes David Bowie tick, but it's not trying to!

Mild spoilers follow

Taking a page from Citizen Kane, Haynes constructs a story about a journalist (Christian Bale) tasked with tracking down a British rock star named Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) who disappeared ten years earlier. Bale, interviewing Slade's former manager, his ex-wife, and a fellow rocker played by Ewan McGregor, attempts to piece together a profile of the vanished Slade.

But the difference between Goldmine and Kane is all the difference in the world, because the reporter in Citizen Kane is a faceless non-entity, an absolute cipher who takes the place of an omniscient but colorless narrator whose sole purpose is the provide entry into Kane's life. This is not the case in Velvet Goldmine. Kane is about Kane, but Velvet Goldmine is not about David Bowie, or even his fictional counterpart "Brian Slade," but it is entirely about its reporter character Arthur Stuart, who is not the cipher you might have thought he was walking into the film.

End spoilers

Todd Haynes' films can be perplexing to first-time viewers. I know that I initially was not a fan of this film. It seemed muddled, unfocused. It was not until repeat viewing that I realized that it wasn't the film that was unfocused, it was me, or rather, that my focus was on the wrong point. As soon as I realized what Velvet Goldmine was all about, all the pieces fell into place. I fell in love with its heart, its stellar use of music, its image-based mode of storytelling, and its portrayal of a world left untapped by most movies.

Haynes has said that in his films, the emotions of the storytelling always must come first. Hearing this would no doubt baffle some of his critics, who often describe his films as being about concepts over emotions, more semiotics lessons than stories worth telling. I think this may be because Haynes' movies are so rich with ideas, so clearly conceptual deep in a way that few films are, that they confound those who focus solely on the ideas, not looking at the emotional through-lines that lay right in front of them, through which the films can truly be understood, and loved.

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

NETFLIX PICK OF THE WEEK - The Thin Blue Line

Coming in, just under the wire, it's the Netflix Pick of the Week for Wednesday August 7, 2013!

My pick for this week is Errol Morris' The Thin Blue Line.

My pick for this week is Errol Morris' The Thin Blue Line.

When The Thin Blue Line was released in 1988, its director Errol Morris publicly said that he didn't consider it to be a documentary, that it was instead a "non-fiction film." This is perhaps why the film, despite being one of the most famous, acclaimed, and influential movies of its kind, did not score an Academy Award nomination that year for Best Documentary. But with the shifts and evolutions that have occurred in documentary filmmaking in the past 25 years, and increased prominence of documentary films, The Thin Blue Line may not seem as groundbreaking and unconventional as it once did, but it is not for lack of ambition, nor for lack of artistry.

In 1976, a man named Randall Adams was arrested for the murder of a Dallas police officer. He was convicted and sentenced to death. It wasn't a particularly notable news story at the time, briefly sparking local police fervor that died down when a perp was arrested. After Adams' conviction, the wheels of the justice system began turning in the way they always had. People were killed. People were arrested. Then THOSE people were killed, and so, and so forth. There seemed to be little reason to pay attention to the story of Randall Adams until the documentarian Errol Morris came across his story.

And Morris did what he did best -- he told a story. Several of them, in fact. The Thin Blue Line meticulously reconstructs and reenacts the testimonies of the people involved, in scenes that were highly controversial at the time, using actors, sets, and props to bring to life each person's side of the story -- Adams, the cops, the witnesses. Many of the film's critics railed against this approach. They lambasted the film for failing to maintain "objectivity." As if there could be such a thing. As if such a thing should really be needed in a documentary!

Morris dubbing The Thin Blue Line a "non-fiction film" as opposed to a "documentary" is a telling distinction. Just as in a non-fiction book we don't necessarily expect objectivity -- otherwise, where would be the place of essays? -- The Thin Blue Line is an argument, not a presentation of staid statistics and facts shorn of their spirit. It is a murder mystery, an exploration of the justice system, and a portrait of several fascinating figures, not least among them an odd young man named David Ray Harris.

And in the film's most riveting sequence, Morris holds the audience's attention with nothing more than an audio track and single shot of a tape recorder. And THAT would cause the film's biggest influence -- an enormous influence that lay almost entirely outside of filmmaking, proof (if proof were needed) that art does have an effect on life, that what we put in front of a camera makes a difference in the world, that the act of filming something can fundamentally change the thing being filmed. And for proving that alone, we should all be thankful for The Thin Blue Line.

Saturday, August 3, 2013

Friday Night Lights: One Story, Three Takes - PART TWO: THE MOVIE

MAJOR SPOILERS FOR THE BOOK AND FILM FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS FOLLOW

Immediately upon publication, H.G. Bissinger's Friday Night Lights attracted interest from Hollywood filmmakers. Director, producers, and writers moved in and out. Originally, Alan J. Pakula was attached to direct a screenplay by David S. Ward, who was coming off the hit baseball comedy Major League. At this point, Sam Shepard, during his all-too-brief period as a bankable leading man, was the potential star, presumably as the team's coach. No script by Ward has ever seen the light of day, so it's hard to know for sure what tone the film would have taken, or what elements from the book it would have focused on -- the signing on of Shepard was a good sign, as he naturally projects the air of a plainspoken, intelligent man of rural America, though Ward's output as a screenwriter does little to indicate that the film would be anything other than watchable, but shallow. Later, Richard Linklater (an independent film darling who was also a star Texas high school quarterback) was ready to begin filming, and even began casting and scouting locations before financing fell apart following the box office failure of his film The Newton Boys, leaving cinephiles able only to dream of the mouth-watering possibility of a Linklater-led Lights. As over a decade went by without cameras rolling on any film version of Bissinger's book, its themes and settings were appropriated by off-brand works, like the short-lived NBC series Against the Grain, which ran for a few months in 1993 and is most notable for providing a young Ben Affleck with one of his first big roles, or 1999's film Varsity Blues, which gave the world a Hollywoodized story of a teen on a Texas team facing off against his evil, scenery chewing coach. That film was Lights with the edges sanded off, the nuances made into cartoon morality. The good characters got happy endings, D1 scholarships, Ivy League acceptance letters, and rides off into the sunset while Jon Voight's victory-seeking tyrant of a coach met his comeuppance as his career went up in flames. The state championship trophy is taken home. The boy kisses the girl. The injured players are either miraculously healed or forget their worries when they are given cushy coaching jobs. It was popular, and it was pabulum, and it was exactly the kind of movie that fans of Friday Night Lights feared would be made of their beloved book.

It would not be until 2004 that a film version of Bissinger's book would finally be made and released. The directorial reins fell into the hands of one Peter Berg, who, perhaps not-so-coincidentally, was the cousin of H.G. Bissinger. Berg, an actor and sometimes director with two feature film direction credits to his name, did not necessarily seem like the right man for the job, family connections aside. A New York-native who attended elite East Coast prep academies far away from the overstuffed, underfunded public schools of small town Texas, and whose previous films were competent, but perhaps too-slick comedies, Berg's assignment to Friday Night Lights might have indicated a work-for-hire hack-job. Nothing could be further from the truth. Berg's take on Friday Night Lights was a soulful, deeply felt film, one of the most unfairly undervalued major works of the aughts, proving to be silently influential across multiple mediums and inventing or codifying devices and tropes that are widely used nowadays, but were practically unheard of even ten years ago.

As with any adaptation, the artists behind the film version of Friday Night Lights, (primarily Berg, although the final script credited to Berg and David Aaron Cohen, whose contributions may or may not actually appear in the final film) had to pick and choose which elements from the original source they deemed appropriate for the new incarnation of the same story. And the book Friday Night Lights would be a particular challenge to its adaptors, as its sociological vision and telling detours would be either unpresentable or meandering in a 2-hour long movie where everything is moving at the audience at 24 frames per second. In the finished film, just about everything is jettisoned that does not clearly have to do with the 1988 Panthers season, and the team's key players. The history and growth of Odessa would be unexamined, its rival schools and city demographics would be unremarked upon, local team fans, civic leaders, and preachers would be seen, if at all, in the backgrounds of scenes. Some would lament that the film traded in a portrait of an American town in exchange for a typical sports movie, but Berg, in making his version of Friday Night Lights, smartly knew that the key to filmmaking lie in dramatization, and that those elements that the film was superficially cutting from the book were in fact being covertly handled through the surface elements of the film and its more streamlined storyline.

Having found the spine of their movie (the Permian Panthers rising and falling fortunes as they make their way through the 1988 season), Berg and company were now tasked with identifying its protagonists. In doing so, they highlighted a figure of relatively little importance in the book, and made him one of the film's heroes, and its star role: Coach Gary Gaines, played by a top-billed Billy Bob Thornton.

In Bissinger's book, the focus, when it is placed on a particular person, is almost always on one of the teens on the team. Gaines gets several significant passages emphasizing him in the text, but they are dwarfed by the amount of ink spent on say, Mike Winchell, or Boobie Miles. The image that emerges of Gaines from the book is a sympathetic one. Although Bissinger clearly finds something wrong with the fact that Gaines gets paid more than the school principal, the Coach is primarily presented as something of a victim. He is the subject of negative op-eds in the local newspaper, hundreds of letters of hate mail, and cruel taunts offered by disgruntled Panthers fans who don't agree with the way he's been running their beloved team. With his job on the line with every win or loss, and his time almost completely taken up by handling a team of hormonal teenagers, charged with whipping them into a functional unit of world-class athletes, Gaines handles his workload with a level head and a mostly calm demeanor, giving inspirational, softly-spoken speeches to his boys, not rants or shouts. This characterization carries over to the film, but with a far greater chunk of the film than the book being taken up with Gaines' professional and personal life. The story of the film version of Lights can be summed, somewhat incompletely, but not inaccurately, as the story of a coach dealing a football-crazed town, in a way that would be simply not true for the book. Aided by a fully-embodied performance by Thornton, who was then at the heights of his career as an actor, coming shortly after his equally great (and greatly diverse) turns in The Man Who Wasn't There and Bad Santa, the portrait the film presents of Gaines is that of a stoic, but not unemotional man of quiet dignity and gentle strength, the kind of hero scarcely seen in films nowadays, owing more to Gary Cooper in High Noon or Henry Fonda in any number of John Ford films, not least Young Mr. Lincoln, but far more naturalistic than either of those actors usually wore. And Thornton refuses to make Gaines into a cardboard saint. Gaines makes several questionable decisions over the course of the film, decisions that affect other people in negative ways, and while Gaines is acting in his role as coach, he, at times, seems to realize that he is acting more in the interests of the Boosters and fans than his young charges, his eyes showing his questioning of himself, a mixture of regret and indecisiveness. Thornton's scenes in the last act of the film, delivering the what may be the least rah-rah, but most genuinely affecting speech in sports movie history, animatedly running along the sidelines in the final game, and feeling the spirit leave his body as the refs make their final call, may rank up with the greatest performances in the American sports film genre. Sadly, it would seem that the strength of Thornton's performance may be being overlooked in favor of Kyle Chandler's equally great, but more attractive performance as the TV coach, but more on that in a later post.

The other protagonists of the film are likewise taken from the book, and are rather easily identifiable, in that they are the characters whose home life the audience is shown. While the film shines a spotlight on several of the real-life players, including Ivory Christian, Brian Chavez, and a relatively minor character from the book, younger player Chris Comer (Jerrod McDougal is entirely removed from the film), only Boobie Miles, Mike Winchell, and to a lesser extent, Don Billingsley, can be termed true protagonists. This can be seen, subtly but clearly once noticed, in the earliest moments of the film, as Mike and Boobie both receive brief scenes before they join the rest of the team outside the stadium for the season's first practice, Mike eating breakfast while being verbally prepped by his fragile mother, and Boobie jogging down the street while being worshipped by adoring children like a rock star. Throughout the film, Boobie and Mike's journeys provide the film with a more emotionally connective through-line than Gaines' more restrained storyline. Played by Derek Luke, Boobie Miles remains, as in the book, the tragic hero at the center of Friday Night Lights, although in the film version he shares his duties as heart-and-soul with Mike Winchell. Berg and Luke show the bravado and the confidence of the young running back at the beginning of the season, and even as he boasts and gloats, the viewer remains on his side, feeding off the charisma and charm of Luke's performance. His performance becomes more complex as Boobie's emotional toughness is tested following his pivotal knee injury, and it is here that Luke's heartfelt performance really shines, as Boobie reacts to the greatest setback in his life with incredulousness, then anger, then deep sadness, breaking down in his car, crying his eyes out while wondering aloud to his uncle "What am I gonna do if I can't play football. I'm not good at nothin'!" Those who criticized the film for being too soft on the high school football culture must have stepped out for popcorn during that scene, as well as the scene where Boobie silently observes a black garbageman with both terror and resignation, seeing, like Ebenezer Scrooge confronted with his own grave, a dark vision of his possible future. The film's football scenes are well-choreographed and shot, but it is in these quieter scenes that Friday Night Lights really comes alive.

The other protagonists of the film are likewise taken from the book, and are rather easily identifiable, in that they are the characters whose home life the audience is shown. While the film shines a spotlight on several of the real-life players, including Ivory Christian, Brian Chavez, and a relatively minor character from the book, younger player Chris Comer (Jerrod McDougal is entirely removed from the film), only Boobie Miles, Mike Winchell, and to a lesser extent, Don Billingsley, can be termed true protagonists. This can be seen, subtly but clearly once noticed, in the earliest moments of the film, as Mike and Boobie both receive brief scenes before they join the rest of the team outside the stadium for the season's first practice, Mike eating breakfast while being verbally prepped by his fragile mother, and Boobie jogging down the street while being worshipped by adoring children like a rock star. Throughout the film, Boobie and Mike's journeys provide the film with a more emotionally connective through-line than Gaines' more restrained storyline. Played by Derek Luke, Boobie Miles remains, as in the book, the tragic hero at the center of Friday Night Lights, although in the film version he shares his duties as heart-and-soul with Mike Winchell. Berg and Luke show the bravado and the confidence of the young running back at the beginning of the season, and even as he boasts and gloats, the viewer remains on his side, feeding off the charisma and charm of Luke's performance. His performance becomes more complex as Boobie's emotional toughness is tested following his pivotal knee injury, and it is here that Luke's heartfelt performance really shines, as Boobie reacts to the greatest setback in his life with incredulousness, then anger, then deep sadness, breaking down in his car, crying his eyes out while wondering aloud to his uncle "What am I gonna do if I can't play football. I'm not good at nothin'!" Those who criticized the film for being too soft on the high school football culture must have stepped out for popcorn during that scene, as well as the scene where Boobie silently observes a black garbageman with both terror and resignation, seeing, like Ebenezer Scrooge confronted with his own grave, a dark vision of his possible future. The film's football scenes are well-choreographed and shot, but it is in these quieter scenes that Friday Night Lights really comes alive.

Likewise, Lucas Black's interpretation of Mike Winchell is an intensely, at times uncomfortably, emotional piece of acting. While Derek Luke at least gets to strut and puff his chest as Boobie Miles, flashily showing off his acting muscles in an in-character way, Black plays one of the most low-key and unshowy leading characters in a Hollywood film in recent memory. Winchell, as in the book, is quiet and gloomily private. While the omniscience of the film camera provides the audience with a closer look at Winchell and his inner-life than the non-fiction book was able to, it still refrains from giving Mike big, out-of-character monologues or expository voice over narration. Mike's most revealing moments in the film are a brief phone conversation with his brother that we can only hear one side of, a few short comments delivered to his teammates in the movie's final big game, one scene that solely consists of Winchell crying in the locker room following a loss, and, most of all, silent looks, expressions, and glances. Black is a supreme underplayer, in the best sense of the word, showing that acting is as much about reacting as it is about big moments, and that it is possible to simply exist as your character in a moment, breathing and moving as they would, drawing in the viewer with its verisimilitude. Black, in a cast full of unbelievably strong performers, deserves the MVP title, and with any luck, will at some point in his career find a role that rivals his turn, at age only 21, as Mike Winchell.

Other characters get their moments in the sun, most notably Garret Hedlund as Don Billingsley, whose character arc revolves entirely around his relationship with his father, Charlie (played by country music star Tim McGraw), in a role that is greater emphasized than in the book. Berg's script makes significant additions and changes to these two characters, departures from reality that change the nature of their relationship, and the audience's takeaway from it. As described by Bissinger, Charlie Billingsley is a drunken ne'er-do-well who gained a reputation as a hell-raiser while still in high school, and has been successfully living up to it since then, twenty years down the road. His relationship with his son is an irresponsible one, with Charlie staying up all night, partying and drinking with his 17-year-old son. But it is not abusive. This is where Berg makes one of his biggest changes from the book, and from real life. As played by McGraw, Charlie Billingsley crosses the line from irresponsible, to downright combative. In two scenes early on, Billingsley Sr., while intoxicated, beats his son for not living up to his expectations as a football player. Later, after the Panthers lose a crucial game to their arch-rivals Midland Lee, Charlie kicks out the windows of his sons' car, in a scene completely constructed out of thin air by Berg and Cohen. This is likely the most irresponsible change that Berg made in adapted Friday Night Lights, linking a real man to a fabricated list of sins, and it is no surprise that H.G. Bissinger reported that Don and Charlie Billingsley refused to speak to him following the release of the film. Others include Brian Chavez, drastically reduced in importance from the book, and Ivory Christian, played in a near-silent performance by former Texas Longhorns linebacker Lee Jackson.

But while the performances in the film are wonderful, down to the briefest extra roles and one-line bit parts essayed by Odessa natives and amateur actors, it is in Berg's direction that Friday Night Lights proves itself exceptional. Berg announces himself as visual stylist to rank among the best of his contemporaries. Lights, although filmed largely on the kind of handheld digital cameras most associated with increasingly popular faux-documentary style, creates a largely impressionistic mode of storytelling, aiming not for physical realism per se, but a psychological and emotional realism. The cinematography, courtesy of Tobias A. Schliessler, who for some reason has gone on to do nothing worth watching, is a masterwork, filming the football scenes with a tough, battle-like physicality that owes more to Saving Private Ryan than ESPN sports highlights, and the home scenes with an amazing intimacy. Berg and Schliessler perfectly capture the sun-soaked sands of West Texas at dawn just as much as it captures the clear night skies hanging above the astroturf on fall's Friday nights. Berg's camera catches stray moments, little shots here and there than infinitely expand the world of the film beyond the main plot, such as the wordless shot of a mascot comforting a crying cheerleader after a loss and imbues with them a Terrence Malick-esque humaneness a few years before being Malickian was in vogue. Berg knows how to let the camera linger on a single image, images like a football resting a mere inch away from the end zone, a potent reminder of the desperation of defeat.

But while the performances in the film are wonderful, down to the briefest extra roles and one-line bit parts essayed by Odessa natives and amateur actors, it is in Berg's direction that Friday Night Lights proves itself exceptional. Berg announces himself as visual stylist to rank among the best of his contemporaries. Lights, although filmed largely on the kind of handheld digital cameras most associated with increasingly popular faux-documentary style, creates a largely impressionistic mode of storytelling, aiming not for physical realism per se, but a psychological and emotional realism. The cinematography, courtesy of Tobias A. Schliessler, who for some reason has gone on to do nothing worth watching, is a masterwork, filming the football scenes with a tough, battle-like physicality that owes more to Saving Private Ryan than ESPN sports highlights, and the home scenes with an amazing intimacy. Berg and Schliessler perfectly capture the sun-soaked sands of West Texas at dawn just as much as it captures the clear night skies hanging above the astroturf on fall's Friday nights. Berg's camera catches stray moments, little shots here and there than infinitely expand the world of the film beyond the main plot, such as the wordless shot of a mascot comforting a crying cheerleader after a loss and imbues with them a Terrence Malick-esque humaneness a few years before being Malickian was in vogue. Berg knows how to let the camera linger on a single image, images like a football resting a mere inch away from the end zone, a potent reminder of the desperation of defeat.

Also key are moments humanizing the Dallas team, moments like the team praying during halftime of the state finals and celebrating with true glee their hard-fought win, as if we were being presented with glimpses from an alternate film, a film where the Dallas Carter Cowboys were the heroes of the story, and the Panthers were the villains. It is the small touches like this that open up the film beyond the typical, cliched sports story.

In fact, the overriding mode of the film is to undercut the traditional beats and rhythms of a Hollywood sports film. Expectations of machismo are subverted as we watch the Panthers, who seem invincible on the field, try and fail to suppress their feelings, crying in the locker room as other teammates awkwardly try not to notice. There are none of the usual boilerplate romantic subplots to distract from the core story.* The big game -- the state championship, promoted from real life's state semifinals for greater impact** -- features the team being badly beaten for two quarters, getting an inspirational speech from their coach, coming out for the second half, playing their best, getting down to the last play. . . and falling just short of winning. And to be clear, this isn't a moral victory for the Panthers. They didn't lose but learn something. Nor did they "go the distance," showing the world that they had what it took, a la the original Rocky. No, they started the season ranked number one -- hardly the typical bunch of mismatched underdogs -- made it to the finals, and gave everything they had, and it just wasn't good enough, becomes sometimes you're not good enough. And that's what, if anything, they learn. They set out at the beginning of the season, when hope was high and the future looked bright, to "protect their town," to provide the out-of-work, depressed citizens of Odessa something to be proud of. And they failed, and will never get a chance to redo what they failed at. And when they arrive home, Boobie's knee will still be shattered, the oil workers will still be unemployed, and the maddening craze for Panther football glory will not have ended, just moved back one year. It's a gut punch of an ending.

*Some might argue that a lack of significant roles for women, beyond Connie Britton's thankless tiny role as the supportive coach's wife, may be a fault of the film. But this is a film set in a male driven world, about men, machismo, and masculine roles. It no more needs strong female characters than does 12 Angry Men or Lawrence of Arabia.